Starting and developing an academic program was quite a challenge but exhilarating. The time came to become involved in the community, and it came with a bang. My friend and noted photographer, Baldwin Lee, commented that if you don’t look, you can’t see and looking is difficult.

What I saw in the 1970s was a teenage boy in juvenile detention who hung himself. His crime was not attending school, a status offense.

A status offense is one only a juvenile can commit. There are five primary types of status offenses: truancy, running away, violating curfew, underage consumption and ungovernability.

During that time period in Tennessee, there were more youth in state custody for status offenses than delinquent offenses such as murder, rape, arson and assault. Currently, carjacking is a popular offense.

It struck me that community-based treatment was the mode to follow — a group home in alliance with Lakeshore Mental Health Institute to provide staff and mental health services in a community setting. Along with staff uniquely trained to work with this population, the group home reached out to the community for advice and consent to run the program.

This board was started locally by a business developer whose mother helped with budget issues and meeting accreditation standards of the Joint Committee of Hospitals (JCAH).

This committee was composed of different folks who saw the need to care for these children as the main objective. The group was comprised of doctors, stockbrokers, clergy and others who helped with the many obstacles they would come across.

The first obstacle to overcome was finding a house that could accommodate children. During this adventure, one dismaying event occurred in a church. Two clergy, wearing their clerical collars, and I went to speak at a church where we were unceremoniously asked to leave before we even got the opportunity to speak. Note, the church invited us.

We did our best to address every community’s concern about the house for our children being located in their neighborhood.

An interesting aside to this first obstacle is that after a few years, neighbors were leaving their keys with us to check their houses while gone on vacation, even having the children water plants in their absence.

A serious source of opposition was from the juvenile court and the neighborhoods themselves.

The juvenile court system was building a regional center at that time and feared losing grant possibilities due to the existence of the group home.

The neighborhoods feared a reduction in property values which never materialized in those neighborhoods where group homes were located due to the diligent efforts of group home staff.

The house that served as our group home is in Old North Knoxville and currently has a very high value.

The group started and served children for 10 years. These youths averaged nine petitions each and the program had an 80% success rate over the 10 years.

UT Knoxville Chancellor Jack Reece and I went to Nashville to try and save the program with no luck.

Santayana said, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

So, how this history fits with mental health and correctional needs in 2024 is most important!

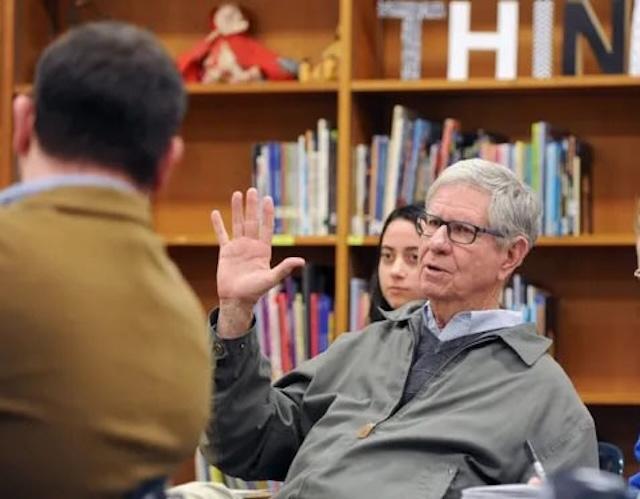

Bob Kronick is professor emeritus University of Tennessee. Bob welcomes your comments or questions to rkronick@utk.edu.