Inskip owes its name to the fortunate collaboration of two men: a Southern industrialist and railroad tycoon and a northern evangelist and religious campground organizer of renown.

The railroad tycoon was Col. Charles M McGhee (1828-1907). Born on his father’s 1,500-acre plantation in Monroe County, McGhee graduated from East Tennessee University (1846) and settled in Knoxville to develop one of the city’s first suburbs (Mechanicsville); co-own the Knoxville Woolen Mills, which grew to employ 900 workers; establish the People’s Bank and to become an influential director of the East Tennessee, Virginia and Georgia Railroad. During the era of rapid consolidation of the various railroads, which would become the Southern Railway, he was the contact with New York financiers who backed the vast expansion.

In 1871, after the Civil War, McGhee acquired the Knoxville and Kentucky Railroad (later the Knoxville and Ohio) which, due largely to the panic of 1857, had languished with only nine miles of track built – far short of its goal of reaching the Kentucky border. But, one of the K&K’s stops was at a small north Knox County community which at the time had one church, a one-room and a two-room school and the village grocery which housed the post office.

It was Col. McGhee and his railroad which facilitated transportation for Knoxvillians who had been attending campground meetings in Fountain City Park since the 1830s and now found the new location more convenient.

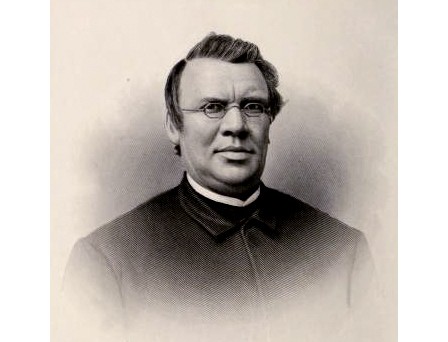

Leaders in Church Street Methodist Church had been appointed to a committee to provide the site for the first National Camp Meeting Association (NCMA) venture in Knoxville. Scheduled to begin on Sept. 21, 1872, its importance called for the president of the organization, the Rev. John S. Inskip (1816-1884), to be the featured evangelist.

Inskip had immigrated from Great Britain with his parents when he was only 4 years old. After he was educated as a Methodist minister, he served as pastor of several churches throughout the Northeast and had become a leader of the Holiness Movement. He had also established a national reputation as a traveling evangelist originally based in New York and northern New Jersey.

The charismatic Rev. Inskip was almost poetically described by his contemporary, the Rev. George Watson: “Inskip impressed me all of the time as a warrior and leader, a man of unbounded magnetism, a Bonaparte in the Holy Ghost. He could sway thousands of people as easily as a lion sways a cat. He could arouse a vast audience into a foaming sea of enthusiasm, with waves of white-capped excitement breaking on the shore, and in a few moments could quell them to a placid lake, whose tiny ripples of low breathed prayer were hardly audible on the beach.”

NCMA had a worthy plan. According to a former Inskip Methodist Church minister, the Rev. David Lewis, “(Many Methodist ministers) felt that the nation following the Civil War period was in terrible condition. Hatred and animosity was still going on between the north and the south. They began holding these Camp Meetings where they traveled across the country and held Christian gatherings. They would set up tents and hold prayer sessions and lessons for 10 days, then move on to the next stop.”

Some of the most prominent local religious leaders were appointed to the committee to prepare for the 1872 meeting: Marcus D. Bearden, David Richards, Leonidas C. Houk, Capt. William Rule, Charles M. McGhee and William G. “Parson” Brownlow.

They had chosen a plot on Col. Arthur Crozier’s farm, four miles from Knoxville on the K&K Railroad and had secured a 24 x 100 foot tent for the event. The trains were scheduled to run each day as often as necessary to accommodate the public.

The meeting itself was planned as a week-long inspirational event. N.L. Hicks (2000) described a typical day at a camp meeting: “Morning light finds the visitors astir. After breakfast the early morning service takes place in the church (tent). About 11 o’clock another sermon is preached. In the afternoon at 3 o’clock services are again held, concluding with the service at dusk. After the last meeting is over, all retire to the grove to engage in a time of silent prayer.”

The meeting was very successful. At the closing service on Sunday morning about 6,000 people attended and 3,000 attended that evening.

The committee planned another meeting for the following year and they were so optimistic that they bought the grounds, some 21 acres, and decided to build a tabernacle which would seat 3,000 and to make other needed improvements.

The camp meetings left such an impression that the area became known as Inskip. People would refer to the “Inskip Stop” or “Inskip Place” and, eventually, just to Inskip.

The Rev. John S. Inskip continued his evangelistic ministry and held services from his native New York to new fields in California. He passed away on March 3, 1884, at age 67 and was interred in the famous Brooklyn (New York) Green-wood Cemetery. Ironically, Green-wood provided the model for Dr. R. N. Kesterson when he established our Greenwood Cemetery as a final resting place for his beloved son who died of a childhood disease at only 3 years of age.

Author’s Note: Thanks to N.L. Hicks’ “A History of Fountain City (with sections on Inskip and Smithwood)” (2000), Mrs. Morris L. Snow’s “The Early History of Inskip Methodist Church” (1957), Samuel Avery-Quinn’s thesis “From parlor to forest temple: an historical anthropology of the early landscapes of the National Camp-Meeting Association (1867-1871)” (2011) and Jim Matheny’s “Why-do-they-call-it-that?” (Station WBIR, June 25, 2014).