Father and son Fred J. Conner and Thomas W. Conner submitted an article to the 1928 Central High School annual, the Sequoyah, entitled “History of Fountain City.”

The four-page article discusses John Adair, Fort Adair, The Campgrounds (later Fountain City Park), the Fountain Head Railway (the Dummy Line) and other landmarks. Only a few paragraphs discuss events that occurred in Fountain City during the Civil War. However, those events appear in no other histories, not even in Digby Seymour’s definitive book on the war in Knoxville and vicinity, “Divided Loyalties.” The episodes the Conners describe came after the Battle of Fort Sanders (Nov. 29, 1863).

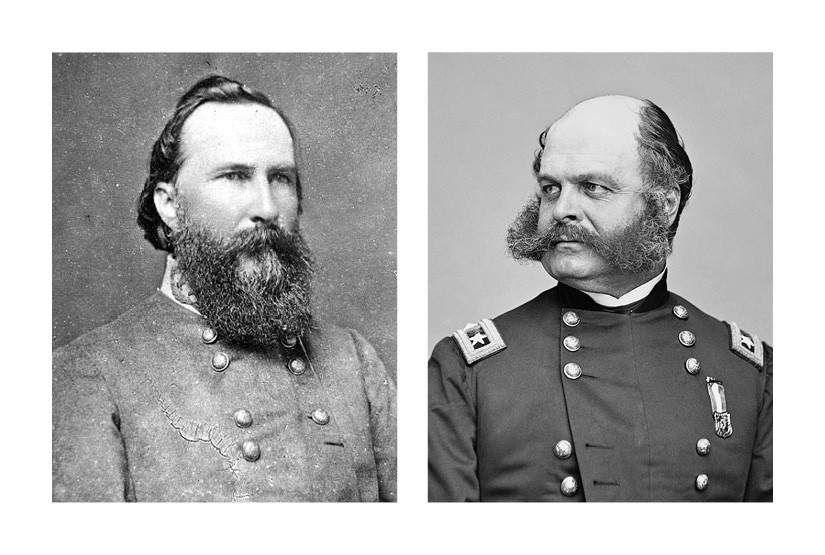

Union Gen. Ambrose Burnside’s long-delayed capture and occupation of Knoxville began on Aug. 16, 1863, when he left his camps at Nicholasville, Kentucky (south of Lexington), to make the difficult 220-mile march through the mountains of southeast Kentucky and northeast Tennessee. His 15,000 troops reached the city on Sept. 3 and occupied it without opposition as the Confederates had abandoned the city earlier.

After the battle of Chickamauga, Gen. Braxton Bragg, commanding the Confederates around Chattanooga, felt that chasing Burnside back to Kentucky would ease the pressure on him at Chattanooga. He ordered Gen. James Longstreet with 12,000 men to march on Knoxville and recapture the city.

After much delay performing reconnaissance and the preparations for battle and because of the terrible weather during the coldest winter in recent history, Longstreet scheduled the assault on Fort Sanders, where he thought Burnside was most vulnerable.

These are the salient facts: The formidable eminence where the fort stood was surrounded by a ditch 6-8 feet in depth but it appeared to be only 3-4 feet deep as planks not visible from a distance permitted troops to cross it with apparent ease. The earthen walls were 13 feet high in most places with cotton bales topping them wrapped in rawhide to prevent fire and to further protect the riflemen. Water was poured down the side of the earthen fort and it had frozen overnight. Recycled telegraph wire had been interwoven between the numerous 18-inch stumps in front of the bastion to trip and delay the attackers. To complicate the attack the leaders decided that scaling ladders would not be needed and none were available.

Seymour’s book describes the scene at dawn on Nov. 29, 1863:

“The rapid advance in almost complete darkness over terrain filled with obstacles and converging furrows brought the attacking force in a packed mass whose officers could no longer distinguish their own men. Hesitating only momentarily, the men swarmed into the ditch which they had been told was no more than four feet deep. They expected to get a toe hold on the berme and scale the parapet with one leap. But as they surged into the ditch, they discovered to their horror that in places it was more than eleven feet deep, the embankment was slippery and icy, the berme had been cut away, and the parapet had been built up very high with cotton bales. Many of the men, not knowing what else to do, fired into the embrasures at any of the Federals foolish enough to show their heads.”

In 20 minutes the battle was over. There was nothing to do but surrender. Longstreet had lost over 800 men (killed, wounded and missing), Burnside only 13. Longstreet took a few days to assemble his wounded men and retreated through Strawberry Plains and Jefferson City to Russellville where he spent two miserably cold months before he proceeded back to the battlefields of Virginia.

The Conners describe these events that occurred after the battle:

“During the Civil War, Fountain City, as well as other sections of the country, had its experiences. While there were no battles fought nearer than Fort Sanders, yet one of General Bragg’s divisions, when forced to retreat from Kentucky, camped in Fountain City.

“It was commanded by General (Danville) Ledbetter, whose headquarters were almost where Mr. J.W. Williams’ barn now stands. After the Battle of Fort Sanders, most of General Longstreet’s army, in retreating to Virginia, passed through what is now Smithwood. They went east along the Tazewell Pike. (Emphasis added.) This was quite an exciting spectacle to the community, and especially to the children, to see an army in full retreat. Their horses were in very poor condition, and they were not able to travel any distance. They would stop, the man on the horse would get off and walk on; another man would come along and get on the horse and go on.

“The only real exciting experience occurring during the war was on the morning after the retreat of the Confederates. The Federals were sent out in scouting parties. There was a Confederate officer, who with three privates, out near Halls Cross Roads, which is north of Fountain City, getting horses to use in the Confederate army. They, not knowing which way the battle had turned, were on their way back toward town. When they were near Smithwood, they discovered to their consternation, that they were right on a detachment of Federals, who opened fire on them at once. They turned east onto the Tazewell Pike and quite a race followed.”

“General Burnside and his staff came out through Fountain City reconnoitering and he made quite an impression on the people by his kindliness, pleasantness and gentlemanly behavior. The report got out after the retreat of Longstreet that he was going to return by way of the Tazewell Pike. On receiving the information, the Federals barricaded the road at Greenway Station by chopping the trees down on either side of the road and felling them into it. They also planted cannon on each side of the road just north of the station. Longstreet did not return; but this is the nearest Fountain City came to having a battle.”

(Author’s Note: Any additional information on Fountain City during the Civil War would be welcomed.)

Jim Tumblin, retired optometrist and active historian, writes a monthly series called “Fountain City: Places That Made a Difference” for KnoxTNToday.com.