If Mildred E. Doyle were Knox County Schools superintendent today, she wouldn’t be afraid of any ol’ mouse – or “Maus” – and she probably would have urged her community not to ban Art Spiegelman’s Pulitzer Prize-winning graphic novel.

Doyle, the legendary schools superintendent who served from 1946 to 1976, faced a censorship controversy of her own in 1969 when the Knox County Board of Education voted to remove “The Catcher in the Rye” by J.D. Salinger from high-school reading lists. She sided with the experts – educators – who believed the book was important for secondary-school students to read.

Mildred E. Doyle (1904-1989) served as superintendent of Knox County Schools from 1946 to 1976. (File photo)

While censorship won out in 1969, as it did recently in McMinn County, Doyle’s strong personality – if amplified by social media – might have changed the course of events. For most of her 52-year career in education, Doyle received widespread public support.

Born Dec. 27, 1904, to Charter E. and Illia Burnett Doyle, Mildred Eloise Doyle had 10 siblings – five sisters and five brothers – who survived to adulthood. Circa 1912, the family moved from their 20-acre farm off Neubert Springs Road in South Knoxville to the nearby 200-acre spread on Martin Mill Pike where Charter Doyle had grown up. Both properties were part of an 1800 land grant received by ancestor John Doyle.

“Kellie McGarrh’s Hangin’ in Tough: Mildred E. Doyle, School Superintendent,” written as a dissertation by a University of Tennessee doctoral candidate and published in 2000, and “Mildred Doyle Remembered,” compiled by local educator Benna F.J. van Vuuren and printed in 2011, are available from the Knox County Public Library. Despite the differences in approach and even some details, they paint a picture of a fascinating, passionate, progressive, humorous, intelligent, generous and admired East Tennessean. She was the first and still only female schools superintendent in Knox County history, and her 30-year tenure remains unmatched.

The Doyle family loved athletics, and Mildred’s dream from an early age was to become a professional ballplayer. She played baseball, softball, tennis and basketball at every opportunity. She also did chores on the family farm and considered herself a tomboy.

Doyle attended the two-room Moore’s School through sixth grade and entered Young High School in seventh grade. She was a guard on the girls’ basketball team her freshman through senior years. The team played in bloomers.

At the time, graduates received a provisional one-year teaching certificate along with a diploma, but Doyle didn’t want to be an “old-maid schoolteacher.” She decided to go to Maryville College, primarily because it had a women’s basketball team. While she excelled on the court, she didn’t apply herself to academics, and she also racked up several demerits. At the end of her freshman year she was asked to leave the school. In 1965, Maryville College bestowed on her an honorary doctorate for her contributions to education and the community.

Like his father before him, Charter Doyle was a “judge” in the County Court, the predecessor of Knox County Commission. The judges, or “squires,” held a great deal of power over the schools.

In that era, married women were not allowed to teach. In 1924, when daughter Lois married and was forced to quit her job at Anderson School, Judge Doyle suggested that Mildred apply for the vacancy – her teaching certificate was still in effect. She taught third, fourth and fifth grade for a year and then was transferred to Vestal Grammar School to teach fourth and fifth grades.

To renew her certificate, she had to commit to finish college, so she started taking courses at UT each summer. After three years of teaching at Vestal, the principal’s position became open and she applied. Despite protests from the community – including accusations of her being a “flapper” – she was appointed principal. She reportedly loved her stint at Vestal but eventually left to become a supervisor with the Central Office. Traveling to different schools throughout the county opened her eyes to deplorable conditions in many rural schools, and she sought to become the schools superintendent in 1946. In those days, the position was appointed, but after her second term new laws demanded an election for the office. She won handily for the next 20-plus years.

Doyle brought the school system into the 20th century, both physically and academically. She earned her bachelor’s degree in 1940, double majoring in history and education, and her master’s in educational administration and supervision in 1944. She pressed for all teachers to earn college degrees and raised the quality of the county’s teaching staff.

When Doyle started as superintendent, high school teachers had a higher pay scale than elementary teachers. Coincidentally, or not, elementary teachers were predominantly female, while males dominated high school classrooms. She pushed for a single salary scale, and the BOE approved it. While she didn’t consider herself a feminist, the result of her action was that pay increased for women teachers.

Doyle also crusaded to improve the infrastructure of the schools. She convinced the County Court to fund new buildings and renovations to older ones. Some facilities were still only one or two rooms, and several did not have indoor plumbing. She got county residents to understand that there was a vast disparity between the haves and the have-nots and come together to improve education for the poorest schools.

She wasn’t able to rest on her laurels of the 1950s because in the early 1960s, the city of Knoxville annexed a huge chunk of suburbs surrounding the downtown area, taking most of her new schools. Doyle and her staff worked hard before the schools’ shift took effect and transferred the best teachers to schools remaining under county supervision.

With the population growth of the 1960s came the need for more schools. In 1966, Doyle broke ground on Tipton Station Road on the county’s first comprehensive high school. Named Doyle High School in honor of the superintendent and her family, it was officially dedicated on April 12, 1968, with UT President Andy Holt as the keynote speaker. Her last building project was Farragut High School, completed in 1976.

In 1975, Doyle started talking about retiring after the next school year, and she maneuvered to make her protégé, Beecher Clapp, her successor. But while she was a respected political animal, Clapp was unknown and didn’t have the charismatic personality of his mentor. As her peers in the county Republican Party expressed their doubts about Clapp winning an election, Doyle begrudgingly rethought her plan and ended up deciding not to retire. She vied against Democratic candidate Earl Hoffmeister in the 1976 election – and lost. Many theorized that her uncharacteristic move of changing her mind was what ended the public’s confidence in her.

Others thought that it was the presentation of a gold Cadillac as a retirement gift from county teachers – relabeled as a birthday present – that soured her supporters.

Doyle was shocked, as was most of the county, at her loss.

In her retirement, however, she continued to work to help the students of Knox County. She was behind an alternative school for students who had been expelled, and she advocated for girls who got pregnant so that they could have childcare while they continued their education.

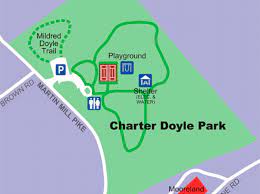

In 1983, she donated 26 acres on Martin Mill Pike that she had bought from her aunt in 1950 to the city and county for use as a park. She wanted it named Charter E. Doyle Park in honor of her late father, but most South Knoxvillians regard it as “her” park.

Doyle was respected not only locally but also on the state and national levels. She was considered for the U.S. Education Secretary. She served on the state textbook commission and helped to create groundbreaking curricula.

She was beloved for her homespun sense of humor, and her private generosity improved the lives of many students.

She received many accolades for her work in education, but the honor that pleased her most was being named to the Knoxville Sports Hall of Fame on June 25, 1983, “in recognition of outstanding character and performance in the field of athletics.”

Doyle loved travel and music and often included Broadway shows on her trips to conferences in New England. She also loved watching baseball on television and trips to Florida to watch spring training.

Until 1961, Doyle shared the family homeplace with her brother, William D., aka “Pinky.” She moved to Island Home Park to live with her friend and assistant, Mildred Patterson, after Patterson’s husband died and she had trouble paying the mortgage.

Diagnosed with bone cancer in 1984, Doyle died at home on May 6, 1989.

Betsy Pickle is a veteran writer and editor who particularly enjoys highlighting South Knoxville.