On June 11, 1792, William Blount, Governor of the Southwest Territory, carved out the boundaries of both Knox and Jefferson counties, effectively bringing government business closer to the people of the region. This Saturday marks 230 years since the counties’ founding. Knox County Mayor Glenn Jacobs with Knox County Library and Parks and Rec will host two celebrations from 5-6 p.m. to honor the momentous occasion.

In both Clayton Park (7347 Norris Fwy.) and The Cove at Concord Park (11808 Northshore Drive), the public is invited to enjoy cupcakes and games and activities of the era from 5-6 p.m. The birthday celebrations will be followed by the Second Saturday Concerts with the Paul Beasley Group playing at Clayton Park and Mystic Rhythm Tribe playing at The Cove. The birthday celebrations and the concerts are free and open to the public.

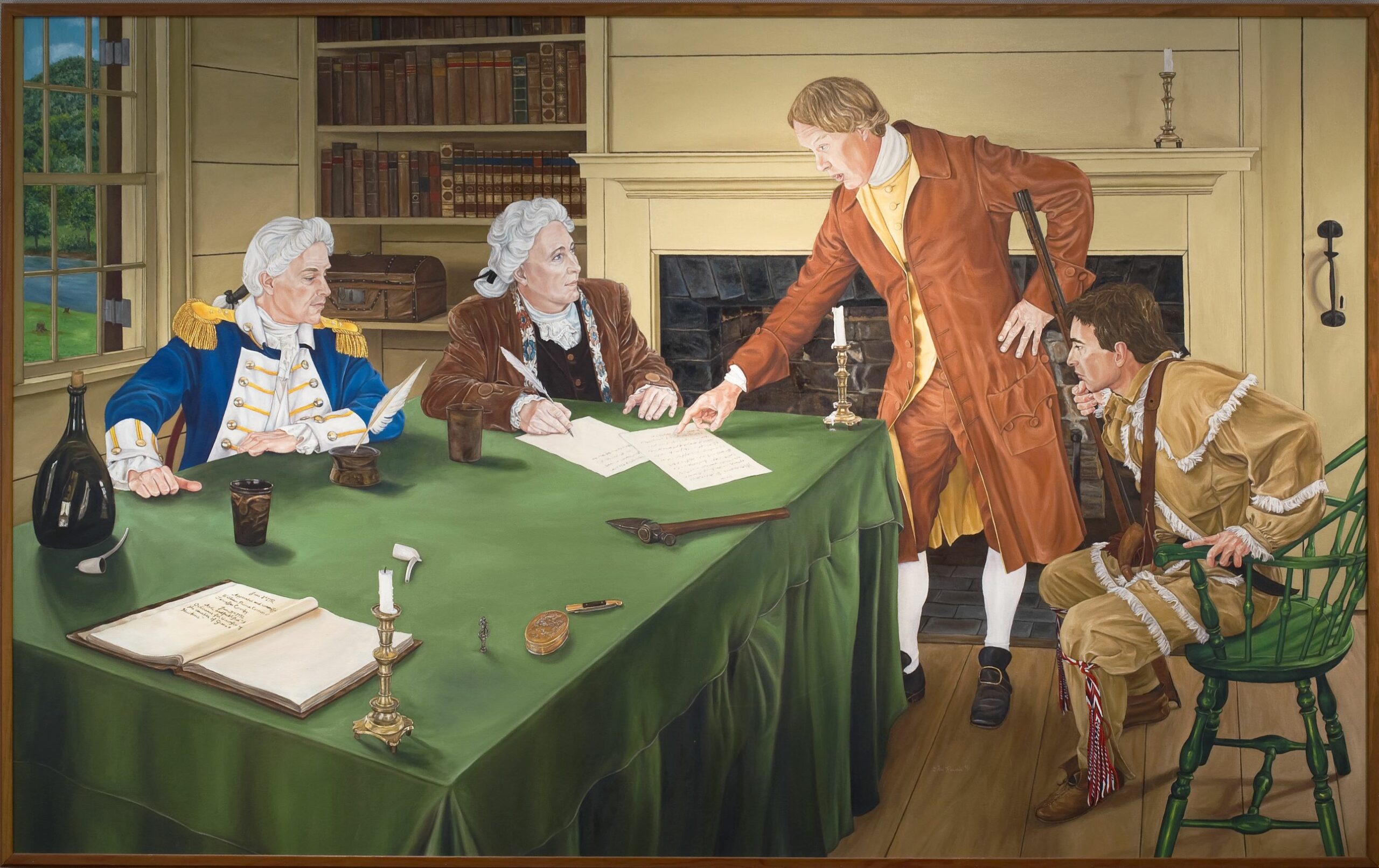

Who is Knox County named for? Henry Knox was the first Secretary of War serving under the Confederation Congress and President Washington from 1785-1794. His contributions to the founding of the United States are immense and include the first victory in the Revolutionary War as the chief artillery officer, driving the British Army from Boston. He accompanied General Washington through most of his major campaigns.

There are nine counties and six cities or towns named for Knox. Knoxville and Knox County, Tennessee, are the most populous.

More about Knox County’s founding written by Danette Welch, KCPL McClung Historical Collection:

In 1792, the portion of the federal government’s western lands that would become Tennessee, especially the area around and beyond Knoxville, still sat on the far edge of the frontier. Then more commonly called the “Southwest Territory” those lands consisted of two separate settlements—the Metro District, along the Cumberland River centered around what is now the Nashville area, and the Washington District, centered along the Holston River in what is now upper East Tennessee — which were separated from the rest of North Carolina by the Appalachian Mountains and from each other by a wide stretch of Indigenous peoples’ lands.

The site of Knoxville and its designation as the capital of the Southwest territory had been settled on since Territorial Gov. William Blount successfully held a monthlong meeting near James White’s fort to create the Treaty of the Holston during May-July 1791. That the new capital of the Territory should also unite the area around it by becoming the seat of a new county was understood from the time James White’s son-in-law Charles McClung began laying out the town.

With Knoxville’s future as capital and a county seat in mind, eight lots of the original 64 were set aside for municipal purposes like courthouses, a jail, military barracks, a school of higher education, and other institutions needed for the business of conducting federal, county and local government. However, as the work of hewing out a town from an “ancient forest of brushwood and grapevines” continued and Territorial Gov. Blount’s additional job as Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the U.S. War Department required much attention to successfully maintaining the treaty for peace with the Cherokee through its ratification and beyond, matters like constructing the buildings of government and creating a new county remained unfinished on the Governor’s agenda.

But by early June 1792, unrest on the frontier had heated to a boiling point. Strengthened by the Western Confederacy of tribes’ defeat of frontier militias and the U.S. Army at the Battle of the Wabash in the Northwest Territory, the Shawnee were working to build a similar force of united tribes throughout the South. Blount could not help but suspect that the conflict between the Southern tribes and American settlers would inevitably lead to a formal war, and that when it did, the Knoxville area would be a center of action.

In the Southwest Territory’s Washington District, Americans were at their most vulnerable when traveling the long, lonely roads between Knoxville and points west and between Knoxville and the county seats at Rogersville and Greeneville, where, as citizens of Hawkins or Greene counties, the settlers in the Knoxville area and beyond were required to travel regularly in order to access all the institutions and functions of their local government.

Carrying mail through the Southwest Territory on a route to/from Knoxville was already considered so dangerous that the pay for a single carrier on a single trip was $50 — enough money to buy six town lots with cash left over — in an era when an average middle-class wage was $65 per year. An open war could only make journeys across Washington District even more dangerous. Cutting down on that travel, and the county-level business that so many Knoxville area settlers had to journey to the county seats so often to conduct, would be strategically wise.

The time to make Knoxville the seat of its own county had come.

Consequently, on June 11, 1792, Blount sat down with a map and dictated to his secretary the boundaries of not just one, but two new counties, bringing the centers of government closer to the people on the frontier. They chose to name those counties after Henry Knox and Thomas Jefferson.

Book suggestions on East Tennessee history:

- The Annals of Tennessee to the End of the Eighteenth Century: G. M. Ramsey (1995)

- The French Broad-Holston Country: A History of Knox County, Tennessee

- East Tennessee Historical Society, Knox County History Committee (1946)

- Goodspeed’s History of Hamilton, Knox and Shelby Counties of Tennessee (1974)

- A History of Knox County Communities (1941)

- Knoxville, Tennessee: A Mountain City in the New South: B. Wheeler (2005)

- Two Centuries of Knox County, Tennessee: A Celebration in Photographs (1992)

- Two Hundred Years of Black Culture in Knoxville, Tennessee, 1791-1991: Robert J. Booker (2003)

- James Mooney’s History, Myths and Sacred Formulas of the Cherokees(1992)

Mary Pom Claiborne is assistant director for marketing, communications and development for the Knox County Public Library.