While most native and many longtime Knoxvillians are familiar with Blount Mansion in downtown Knoxville, the neighboring Craighead-Jackson House is a lesser-known entity. In fact, for a while it was called simply “the white house across the street” from Blount Mansion.

Even the Craighead-Jackson label is misleading. While those two families spent a significant amount of time living in the house, which was built for the Craighead family circa 1818, if the label were to include all of its owners, the name would be the Craighead-Swann-Jackson-Atkins-Aebli House – that’s a mouthful, isn’t it?

Sticking with Craighead-Jackson is certainly easier, especially since the 19th-century building is truly about to make a name for itself. At 10:30 a.m. Wednesday, Sept. 22, there will be a ribbon cutting and celebration of the restoration of the venerable structure next to Blount Mansion, 200 W. Hill Ave.

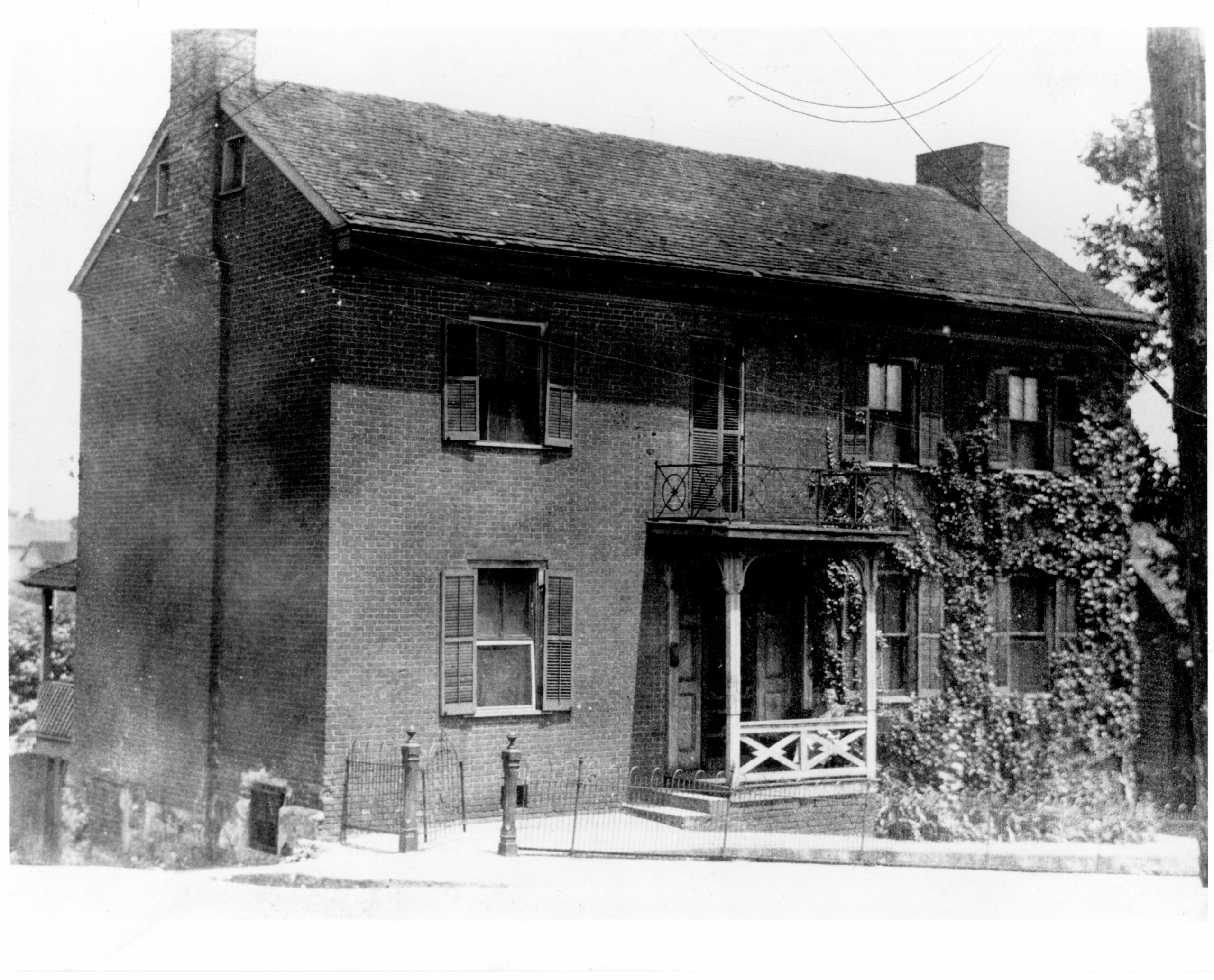

By 1934, a second front entrance had been added.

The restoration was made possible by a $75,000 grant from the Boyd Foundation, and Randy and Jenny Boyd will be on hand for the celebration along with Blount Mansion staff and volunteers. The public is invited to the free event.

Blount Mansion was home to Tennessee’s first governor, William Blount, who was one of the signers of the U.S. Constitution. The Blount Mansion Association was formed in 1925 to preserve and operate the property, and in 1957 the state of Tennessee and the city of Knoxville bought the Craighead-Jackson House and gifted it to the association.

At one point, there was talk of creating a “Pioneer Park” on the eastern edge of downtown, including another historic structure, but urban renewal and the creation of Neyland Drive destroyed that idea.

The house was whitewashed to hide the scars where dilapidated shutters had been removed.

Possession of the C-J House has passed through many hands since 1818. John and Temperance Craighead and their family owned it for 37 years (1818-55). Knoxville Mayor William G. Swan had it for about a year (1855-56) before Dr. George Jackson and his family moved in and stayed for 29 years (1856-85). The Craigheads kept several enslaved African-Americans, and the Jacksons reportedly were abolitionists who maintained a stop on the Underground Railroad.

Investor Samuel Thacker Atkins owned it briefly (1885-86) before selling it to Caspar and Magdelene Aebli, wealthy Swiss immigrants who joined other prosperous German-speaking Swiss in thriving Knoxville, who were the last single family (1886-1922) to live in the house.

The rear additions were demolished when renovations began in 1963.

From 1922 to 1957, the building was divided and rented as dwelling and business spaces. Businesses that operated there included an antique shop, a heating company and a tearoom. Additions that looked like random sheds popped up in the back. The window shutters and back porch were removed, and doors were added. The building deteriorated over time through both use and neglect.

After the property was deeded to the BMA, the group gave it an extensive renovation in 1962-66, spearheaded by Eleanor Keener. Open to the public for several years, it housed the noteworthy Buck Toms silver collection until a couple of avid visitors broke in on a weekend in the 1970s and helped themselves to $100,000 worth of silver. The FBI was called in to help with the investigation, but the silver was never recovered. The remainder of the collection was moved to Crescent Bend.

It was used as Blount Mansion’s visitor center and offices until the 1990s, when a new visitor center was built adjacent to the Gay Street Bridge. At that point, it was primarily utilized for storage.

Michael Jordan, director of marketing and public relations for the BMA, found out about the Boyd Foundation grants and made a pitch for the moon. He ended up with 75,000 greenbacks, which have been used to restore windows, refinish hardwood floors, repair plaster, install an accessible restroom and create a break room. Many of the materials had to be scavenged from shops that carry era-appropriate woodwork and decor. Now it will be used for improved storage as well as offices and meeting space.

The Colonial Revival garden behind the house is being restored with separate funding. Created in 1972 by Atlanta landscape designer Edith Henderson, the garden was commissioned by the Garden Study Club. Magnolia trees encircling the garden eventually choked out other trees, and their roots disrupted brick paths. BMA was allowed by the city to remove the trees in order to restore the garden.

Betsy Pickle is a freelance writer and editor who delves into South Knoxville or downtown history each month.

Restoring the house in the 1960s included integrating new bricks with the old. The new bricks were “aged” using “liquid cow manure.”

Architects believed that the house originally had a back porch, so one was added in the 1960s.