The news moved across social media – as it so quickly does first – that Pat Summitt would be inducted posthumously into the U.S. Olympic & Paralympic Hall of Fame in the Class of 2022. I asked on Twitter if Lady Vol Nation reacted like I did: Wait, she wasn’t in there already?

My second thought: I wished I could have delivered the news to her like I did in 1998 when I made her really mad. But first, the news about the induction.

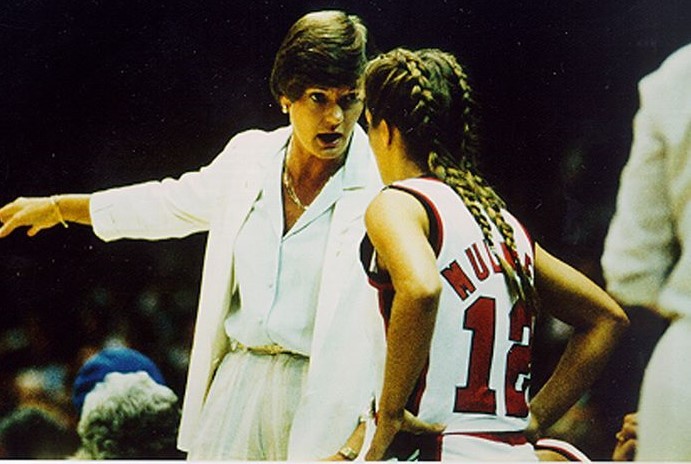

Summitt’s Olympic resume included 11 years with USA Basketball as both a player, assistant coach and head coach, and she became the first U.S. basketball Olympic medalist as a player to lead the United States to Olympic gold as a head coach. At the age of 24, Summitt, who had been the Lady Vols basketball coach for two seasons at that point, served as team co-captain of the 1976 U.S. Olympic Women’s Basketball Team, which won the silver medal in Montreal in the inaugural Olympic women’s tournament. Summitt had to overcome a serious knee injury to make the team while also coaching the Lady Vols, attending graduate school and teaching physical education classes at Tennessee. Just eight years later in 1984, she led the USA team to Olympic gold in Los Angeles as the head coach.

Summitt will be the first woman inducted in the coaching category into the U.S. Olympic & Paralympic Hall of Fame, which seems rather startling at first but there has historically been a dearth of female head coaches leading U.S. Olympic teams.

“Pat Summitt is extremely deserving of this honor as a pioneer in women’s basketball,” USA Basketball CEO Jim Tooley said. “Her commitment to USA Basketball was extraordinary, both as a coach and an athlete. Pat left an indelible mark on not only our game but all of sport.”

The Class of 2022 includes eight individuals, two teams, two legends, one coach and one special contributor. The class will be honored Friday, June 24, at the U.S. Olympic & Paralympic Museum in Colorado Springs, Colorado, and also includes multiple luminaries: Natalie Coughlin (swimming); Muffy Davis (Para alpine skiing and Para-cycling); Mia Hamm (soccer); David Kiley (Para alpine skiing, Para track and field, and wheelchair basketball); Michelle Kwan (figure skating); Michael Phelps (swimming); Lindsey Vonn (alpine skiing), Trischa Zorn-Hudson (Para swimming); 1976 Women’s 4×100 Freestyle Relay Swimming Team; 2002 Paralympic Sled Hockey Team; Gretchen Fraser (legend: alpine skiing); Roger Kingdom (legend: track and field); and Billie Jean King (special contributor).

It will mark Summitt’s eighth hall of fame. She already has been inducted into the Women’s Basketball Hall of Fame; Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame; Tennessee Sports Hall of Fame; Greater Knoxville Sports Hall of Fame; UT Athletics Hall of Fame; UT Martin Athletics Hall of Fame; and Cheatham County Sports Hall of Fame.

News breaks quickly now due to the immediacy of social media. It didn’t do so in 1998. If you will indulge me more of your time and a longer column this week, I will explain how the first time I interacted with Summitt, she was furious with me.

I initially wrote the article in 2011 and reprinted it as the introduction for my book, “The Final Season: The Perseverance of Pat Summitt.” I retained the copyright to my original work, so I will reprint the account here for anyone who hasn’t read it or maybe just wants to read it again. It is written in present tense because Summitt was alive at the time. The story follows.

The first time I called Pat Summitt, I made her mad. True story.

It was 1998, and her team had become celebrities. Led by the three “Meeks”—Chamique Holdsclaw, Tamika Catchings and Semeka Randall – the group made news on and off the court. In February of that year, the team was undefeated and playing a delightful brand of high-octane basketball that packed the arena. It was also one season after the 1997 Cinderella season, which was memorialized forever by HBO. The Lady Vols lost 10 games that year and still managed to win a national title in Cincinnati by beating Notre Dame in the semifinal and Old Dominion in the championship game.

The program hosted a black-tie film premiere of the HBO documentary at the Tennessee Theatre in downtown Knoxville with guests arriving in stretch limousines. This gala event occurred during the 1998 season upon the release of the film that winter. In addition, Pat Summitt had a book coming out called “Reach for the Summit,” which outlined her principles for success. That needed to be reported, too. And there was still a season to cover with home and away games that chewed up the time of the Lady Vols beat writer for the local paper. That was how I came to work late one afternoon in February and ended up calling Summitt.

At the time I was the night editor for the Knoxville News Sentinel on the news side after spending several years as a police and court reporter. That desk position meant I arrived to work with little time before the first deadline, since the early edition of the paper headed across the state and needed to get to the trucks before the evening had actually ended.

The sports department had been tipped off that Pat Summitt was going to be on the cover of Sports Illustrated, and the news side wanted it on page one of the next day’s paper. A photo image of the cover was set to arrive soon. Meanwhile, the sports side was covered up with, well, sports. The beat writer had games to attend and was often on the road trying to handle daily coverage of the team, and news kept popping up that had nothing to do with the court. So, the sports side asked the news side for help ferreting out the Sports Illustrated story. It was early in the last week of February, a Tuesday if my memory is correct. The issue with Summitt on the cover would be for the following Monday, March 2.

Pat Summitt, 1998 cover of Sports Illustrated (Sports Illustrated)

I arrived to work right as these discussions were taking place between the departments. The news reporters were filing their stories that had been gathered that day and would be headed home soon. I was a desk editor that funneled story copy through the night production process so a paper would be delivered the next morning, but I had not stopped writing when called upon to help and welcomed any chance to do so. I also was a lifelong sports fan. That meant I had barely gotten to my desk before I was selected to get the Pat Summitt cover story and get it fast. I had less than two hours to verify the story with SI, interview someone with the magazine, get Summitt’s reaction and file the story to meet deadline.

This was in the 1990s when news reporters called people directly. We didn’t go through a layer of spokespeople. Several prominent officeholders didn’t even have a media contact. If I needed the police chief or sheriff or a judge or the district attorney, I called their office. If it was after hours, I called them at home. This was also before security and access tightened so much – the pre-9/11 world – and newspaper reporters walked directly into offices for interviews. I had been on the night police beat for years and would take doughnuts (no, it’s not a cliché) and coffee to the detectives’ office and sit and chat about major crime cases they were working for follow-up stories, such as homicides and armed robbers on hold-up sprees across the city and county.

So, I wouldn’t think anything about picking up the phone and calling Pat Summitt’s office to determine her whereabouts. I was aware of Deborah Jennings, her longtime media relations chief – she is recognized as the best in the business – and the fact I didn’t call her to set up the interview wasn’t an attempt to circumvent the process. I just wasn’t aware of the process. That wasn’t how the news side operated at the paper.

I also had very little time with the front-page editor saving a big space for the photo, which had now arrived from Sports Illustrated and depicted the classic Summitt stare. The clock was ticking, and my supervisor reminded me that I needed to reach Summitt soon. So, I made the first call. She wasn’t there. If she had been, I would have dashed over to her office to interview her there. I left a message. I waited maybe 10 minutes. I called back.

I wasn’t being rude. Again, this was normal for the news side. We were used to calling officeholders, appointed officials, mayors, governors, etc.

Persistence was standard procedure. Plus, I was running out of time. The business day was coming to a close and university staff members would be leaving to go home. This was before cellphones had taken over communication. People needed to be reached by landlines. The window of contact would soon close for the day.

I repeated this callback process. About the fourth or fifth time, I detected that the secretary answering the phone was getting a tad peeved. Again, this doesn’t cause a news reporter to flinch. I just remained polite, explained it was very important for a page one story and reiterated that I really needed to reach Summitt. A few minutes after the last attempt, my desk phone rang. The person on the other end sounded a lot more peeved than the secretary. It was Summitt.

When the coach confirmed she was speaking to me, a clipped voice said, “What can I do for you, Miss Cornelius?” The emphasis was on Miss and my last name, and the tone was controlled seething. Apparently, she had been very busy that afternoon. I have since learned that Summitt scheduled her day down to the minute. Her calendar was a color-coded chart of places to be, people to see, and phone calls to take. To say the least, my name didn’t appear on her calendar that day.

The secretary, knowing Summitt was very busy, had apparently been alarmed enough by my repeated phone calls to track down Summitt and get her to call me. The conversation was probably something along the lines of “this reporter won’t leave me alone and you really need to call her back now.” As could be expected, Summitt likes to know why people are calling her – especially ones she does not know. That is what the media relations staff do in all arenas, whether sports or politics: they determine who you are and what you want, how much time you need and what the topic will be. But I didn’t have time for that. I had a front page editor asking me every five minutes if that gaping hole in the cover story was going to be filled.

I had never met Summitt. In fact, we had never spoken, not even on the phone. I was a little startled by her tone and thought that the Sports Illustrated cover photo had certainly pegged her. Of course, I now know I had panicked her secretary and Summitt had been pulled out of a previously scheduled meeting of some importance to deal with some pesky reporter. I thanked her for the call back, said she would be on the cover of Sports Illustrated, described it and said I needed her reaction. The cover was a big deal. Female athletes had been on the cover, but she would be the first female coach to grace that page.

The phone went silent. I wondered if we had been disconnected. After a few seconds, a soft voice said, “Can you repeat that?” I did, including the title words “Wizard of Knoxville,” a play on John Wooden being the “Wizard of Westwood” while at UCLA. “Wow,” Summitt said, still with a quiet voice. Clearly, this had stunned her in a good way. Of course, I needed more than one word for my story. So, after she got over the shock, she answered my questions in the tone that is so familiar now – straightforward and engaging. She also credited the players and said any honor she got was shared with them. I have since learned this is common with Summitt, too. She will rarely take credit for anything.

My memories go back to that day with the news in December 2011 when Summitt and Duke coach Mike Krzyzewski had been selected as Sports Illustrated’s Sportswoman and Sportsman of the Year. This was Summitt’s reaction: “Obviously, this is a tremendous honor. I am so privileged to share it with such a great coach in Mike Krzyzewski. During our careers, we have both been fortunate to work with so many talented student-athletes who were driven to excel both on and off the court. For me, this recognition is a direct reflection of the outstanding young women who have worn the orange and white Lady Vol jersey of the University of Tennessee; the coaching staffs I have worked with throughout my career and the supportive administration at UT.” Nearly 14 years had passed between covers for Summitt, but she was essentially unchanged. The credit went to everyone.

Pat Summitt and Mike Krzyzewski, 2011 cover of Sports Illustrated (Sports Illustrated)

Time Inc. Sports Group editor Terry McDonell said, “The voices of those who have been inspired by Pat Summitt and Mike Krzyzewski echo from everywhere and will continue for decades. What they have achieved through their coaching and, more importantly, their teaching places them among history’s transcendent figures. It is an honor to now include them in the select group of Sportsmen and Sportswomen.”

Both are the winningest coaches ever in NCAA Division I men’s and women’s basketball, and both were recognized for that achievement. Krzyzewski reached that pinnacle in December 2011, and Summitt did so in 2005. Both are still adding to their win totals and continue to be admired for how they conduct their lives off the court.

In Summitt’s case, she revealed in August 2011 that she had been diagnosed with early onset dementia and would continue to coach. She and her son, Tyler, have set up The Pat Summitt Foundation to raise awareness of the disease and funds to find a cure. The announcement sparked a “We Back Pat” campaign at the University of Tennessee that was adopted by the SEC for an entire week with men’s and women’s teams using home games in January as a chance to promote the foundation.

Since that first cover in 1998, Summitt has continued to win. The program’s sixth national title came at the end of the 1998 season with a perfect 39-0 record, sparking another book with co-writer Sally Jenkins, Raise the Roof. Two more championship trophies were added in 2007 and 2008.

Summitt has handled having dementia the way she approaches everything in her life – head-on, no “pity party” and in the open. Her mother, Hazel Head, probably liked the 2011 cover over the 1998 one. She remarked in 1998 that she wished the magazine had selected a photo of her daughter that showed her smiling. She got her wish with the 2011 issue, which depicted Summitt, basketball in hand, standing beside an also smiling Krzyzewski.

Maria M. Cornelius and Pat Summitt during an interview in 2009. (Personal photo)

I have one more Summitt story about that 1998 season.

The SEC Tournament was in Columbus, Georgia, that year, and Summitt’s first book, “Reach for the Summit,” was about to be released. The newspaper received an advance copy, and I was asked to review it and interview Summitt. I had also handled the HBO documentary debut in Knoxville and ended up in Kansas City to cover the fans at the Final Four in 1998 for the news side of the paper. Eventually I became the go-to for Lady Vol basketball stories that occurred off the court.

But in Columbus in 1998, I was just a person with a ticket to the SEC Tournament and an advance copy of Summitt’s book in my hand. I saw her sitting in the stands with her assistants and walked over to introduce myself. This was the last week of February, just days after I had persistently called her office about the Sports Illustrated cover, which was starting to reach newsstands. Fans were bringing items over for her to autograph.

I sat in a seat to the side of her and pulled out the book. She looked stunned and said, “Where did you get that?” The book was weeks away from release to the public, so a seemingly random person sitting down and pulling out a copy was understandably surprising. I explained who I was and why I had the book, and once again her tone changed, and she smiled. I then saw the Summitt everyone else meeting her in person had described – warm, engaging, gracious.

I asked if I could interview her about the book later – I had just gotten it, so I had not read it yet – and she smiled and said, “Call my secretary to set it up.”

We both laughed.

Maria M. Cornelius, a writer/editor at Moxley Carmichael since 2013, began writing about the Lady Vols in 1998. In 2016, she published her first book, “The Final Season: The Perseverance of Pat Summitt,” through The University of Tennessee Press. She can be reached at mmcornelius23@gmail.com.