Throw away your car keys, Knoxville. The city administration would rather have you walking, biking or riding one of those heavily-subsidized buses that travel more than half-empty over a handful of fixed routes, every 15 to 30 minutes. Wear comfortable walking shoes. Chances are the bus stop isn’t close to your actual destination.

Or hop on a bike. Never mind your advanced age, infirmity or those breath-taking hills. How do you juggle three bags of groceries on the handle bars? Or the laundry? Saddlebags?

Smart Growth. How do you timely reach three different destinations in one afternoon by bus? It’s hard to beat the door-to-door convenience of an automobile; it’s ready when you are. The social engineers, however, have other plans for our carbon-belching, urban-sprawled society. Their goal is not increased mobility, comfort or personal choice. They want to concentrate density and plan what they’ve named “smart growth” around public transit.

How to achieve this smart growth? Part of our re-education comes from regularly closing roads to host “open-street” festivals or myriad downtown events. Some of those are fun, of course. But they are not travel friendly. Happily, they are temporary.

Other experiments are more concrete. Witness the $25 million transformation of Cumberland Avenue, formerly a U.S. highway handling a lot of traffic, into a “pedestrian-friendly” two-lane street. Business disruption aside, that makes some sense since it goes through a university environment with kids on foot. Drivers, at least, have Neyland Drive as a backup.

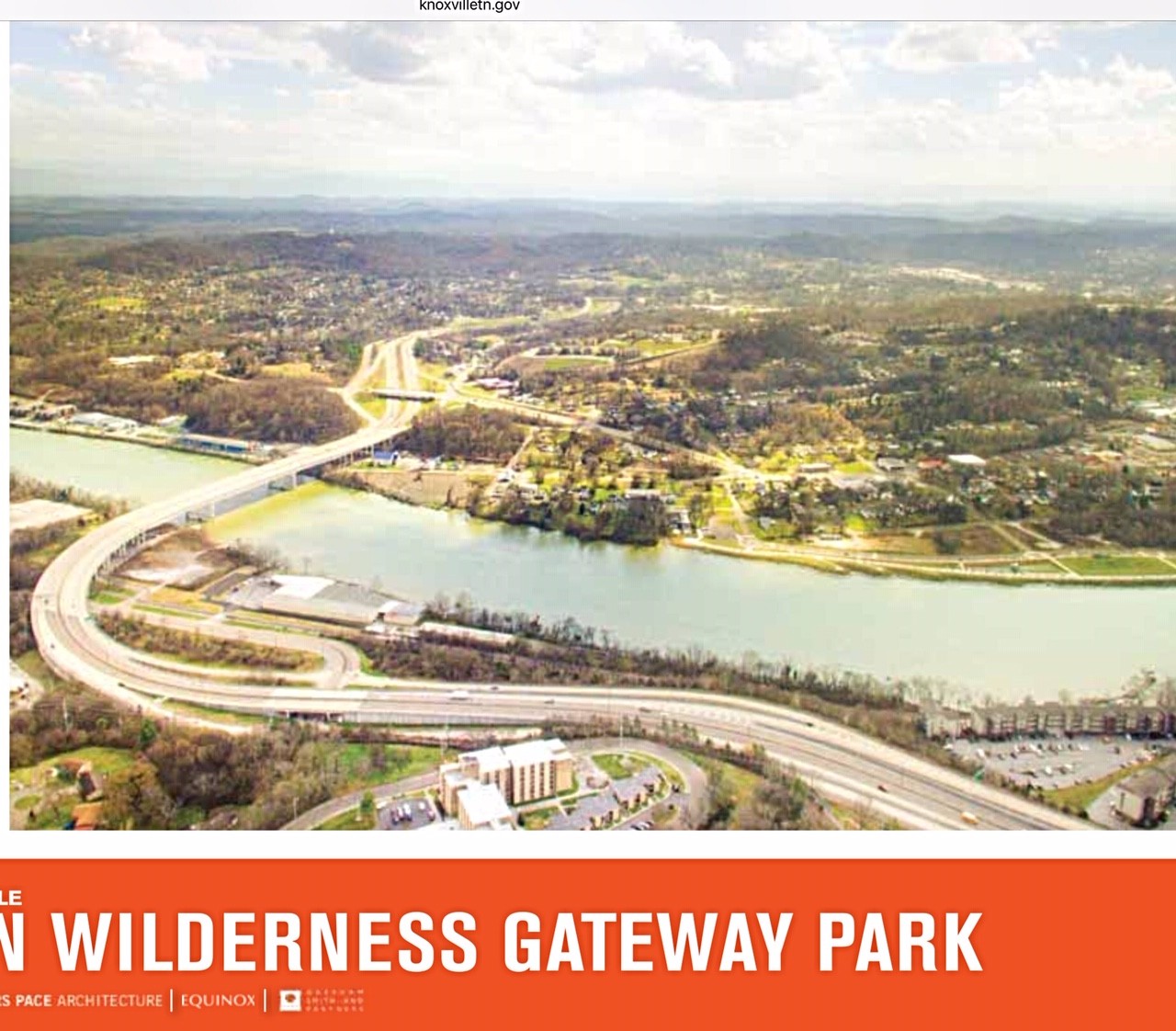

James White Pkwy. Our mayor later decided to convert our $150 million investment in James White Parkway into a “gateway park” leading to the Urban Wilderness trails. A quick vote and the stroke of a pen negated a traffic-alleviating investment, paid for by your federal and state gasoline taxes, to create a playground in the roadbed.

Think about that. Chapman Highway (U.S. Hwy. 441) is already congested during rush hours. It handles over 40,000 cars a day. Any attempt to widen it would wipe out vital parking for businesses that flank this space-constrained route. Impractical.

Over 40 years ago, James White was designed to reroute thru-traffic that normally travels north from Sevierville to I-40 or, alternatively, south toward the mountains. More than half of Chapman’s travelers are not there to shop at local businesses bordering this arterial. Good road design anticipates travel patterns and diverts thru-traffic to an alternate road. Additional congestion is neither good for local commuters or for carbon exhaust reduction. Stop-and-go traffic belches more pollution. So, why do it?

Congestion is a strategy. Can’t entice them to bus? … then force ’em! Clogged roads might get them out of their cars. City engineers have even suggested that TDOT narrow or eliminate travel lanes on Chapman Hwy to further frustrate the already stop-and-go drivers. Maybe substitute a bike lane. Huh?

The answer is revealed by observing progressive cities, like Portland and Seattle, which have intentionally increased auto congestion, in order to frustrate drivers, with the hope of forcing people to shift to mass transit. According to transportation analyst, Randal O’Toole, in his book “Gridlock,” Seattle, Portland and several other west coast cities have been diverting millions of highway improvement funds to build their preferred light-rail alternatives. Accessible multi-use housing was planned to replace auto-mobility suburban growth. Seattle even subsidized the development of residential towers flanking rail lines to encourage the transition. Turns out commuters prefer the convenience of their cars nearly10-to-1 over such mass transit modes. Interrupted or inconvenient truck service can also cause businesses to relocate away from such traffic-congested areas. People who can, vote with their feet – they move. Indeed, author O’Toole reports that nearby Vancouver, Washington, and Salem, Oregon, picked up population fleeing from Portland’s “anti-mobility campaign.”

James White by the numbers. Back to the nullified James White Parkway. The connection from Neyland to the Parkway bridge and the wide-span river-crossing bridge were built around 1983 at a cost of over $100 million (current dollars). Some two miles of Parkway were later added south of the river to the Woodland Avenue exit. Roadwork was halted around 2003, as concerns were raised. After public meetings, a final 4.7-mile segment – which TDOT re-designed in 2013 as a proposed “green route” to minimize impacts to the wilderness area – was ready to be funded (cost estimate $104 million) to complete the Parkway to John Sevier Hwy.

The battle over the road emphasizes the need to adopt a Balanced Approach…rational planning that employs “efficiency” to solve traffic problems, increase safety and harness technology to reduce pollution. With the new Parkway design, the two uses could co-exist. But Mayor Rogero, acting chair of the area TPO, pulled the plug on project funding by removing it from the transportation improvement priority list (TIP).

TDOT estimates the Parkway would relieve some 15,000 cars per day from congested Chapman traffic (which by 2035 is estimated to grow from 41,000 to 66,000 cars per day without the project). Balanced growth was stalled. Instead, a $10 million gateway park is planned for the roadway.

While awaiting the 2019 election, pedal on over to the park…