As promised, at the end of the last installment, here is the discussion and explanation of how I started and ran the University Assisted Community Schools in Knoxville and later in the Sunbright community in Morgan County.

I don’t always know how I got those ideas, but most likely from seeing a need as an opportunity. I had never worked in a school professionally, but I did volunteer in the clinic and coached Destination Imagination for two years when my son was in elementary school. Those were both good experiences to see how needs should be met.

Likewise, I had seen children and families being handled by corrections and mental health in the Department of Children Services.

What I learned at the time was that challenged children weren’t playing. They were watching. Like food deserts, there were child care deserts. I realized that where there were challenged children, there were challenged communities. Where there were challenged communities, there were challenged children.

First, I observed school buildings generally were empty after 3 p.m. This was defended by a state legislator who told me students should not be at school after 3 p.m. I was also told by a civic group that they already paid for schools and why should they do this again.

To the state legislators who agreed, I used a couple of arguments for using the buildings after 3.

I told them the PreK- 5 students needed a place to go for safety. Plus, I argued the temperatures within the buildings were necessarily maintained: warm in the winter so the pipes didn’t freeze and by the same token, cool in the summer. Why not use the buildings so kids can have a safe place to go?

Regarding paying now or paying later, I asked the group of legislators how many of them ate in restaurants, and virtually all of them raised their hands. I then asked if they wanted those restaurant employees to be able to read the sign, “Wash your hands.” Enough said – they got it.

The first superintendent I met with said a flat, “NO!” He didn’t want children in the building after 3. Never give up. According to Edison’s records, he tried 2774 times to reach a working design for an electric light bulb. I didn’t have to make that many tries.

Fortunately, the next superintendent was intrigued and said, “Take any schools you want.” So, in 1990, with no money, but with a group of UT students from Professor Bob Cunningham’s political science class, we began the adventure.

Various students from across the campus but going into medicine played a major role in establishing the Clinic Vols program, a key component of UACS. Their relationships with the children were especially important because these students had rarely seen a physician, some never.

Here are just a few of these UT students and where they are now: Gigi Youngblood, a pediatrician in rural Alabama; Michelle Gourley, a physician in Mt. Sinai Hospital in New York; and Michael Catalana Ph.D., in a psychiatric hospital in Spartanburg. Kimberly Bress and David Marsh are both finishing up at Vanderbilt, an MD in psychiatry and Ph.D. in mechanical engineering, respectively. Jamie Coble was the first to work with the program and is currently a professor in UT’s nuclear engineering department.

You might be asking, “If it’s a community school, where is the community?”

The UACS does its best to determine and meet the community’s needs through the program. That will follow in future installments as I detail the prototype of one of our schools as to how we began to meet and continue to meet the needs in our schools.

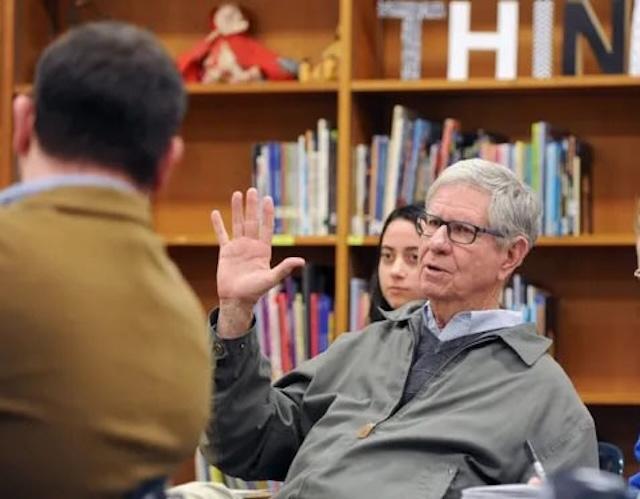

Bob Kronick is professor emeritus University of Tennessee. Bob welcomes your comments or questions to rkronick@utk.edu.